Producers vs. Presenters: Taming the Presentation Deadline Beast

This needs to happen for several reasons.

- All parties need to know the content of the presentations so that presenters do not overlap, contradict, or conflict with each other

- Presentations need to be coherent and valuable for the audience

- Timing needs to be taken into account for realistic agendas

- Slides need to be checked for clarity/mistakes

- Media needs to be tested and procured in advance

- It helps ensure that the event goes smoothly

This doesn't happen for several reasons.

- Presenters are busy

- The event isn't a priority because they have more important/critical/time-sensitive things to do in their day-to-day jobs

- Presenters have turned in presentations last-minute before and everything has worked out

- Content changes may occur on time-sensitive presentations (i.e. first quarter results are announced, acquisitions happen, etc.)

- Presenters are waiting for other co-presenters/key players to contribute

- There is an established culture of "putting together the presentation on the plane", etc.

In our minds, this will be an ongoing struggle, because the reasons for this needing to happen and the reasons why it doesn't happen are both pretty legitimate and need to be balanced in a diplomatic manner.

However, based on our experiences working with clients and other production teams there are certain things you should NOT do.

DO NOT:

Create artificial deadlines: Don't be the event producer who cries wolf. A presenter knows that it's unnecessary to have a finished presentation two months before an event occurs. We once worked with a presentation team that wanted locked-in teleprompter copy (with no changes on-site) MORE THAN ONE MONTH before the event. It was unrealistic and it made it easy for every single presenter to completely disregard the legitimacy of other (more crucial) deadlines.

Ignore deadlines and hope for the best: Presenters should have a good outline of when things are expected of them. Some production companies set the final deadline as "When the presentation is being presented on stage" with no other milestone/check-in points. Deadlines *do* need to be managed, and timetables help set everyone's expectations.

Mismanage the presenters: Think of this like Goldilocks and the Three Event Producers: One micromanages too much, the other isn't attentive enough...and one is just right. Don't be the presentation task-master without a healthy dose of flexibility and diplomacy. We worked with an event producer who was incredibly harsh about presenters getting their stuff in by exact deadlines. Not only did the presenters resent the event producer, but they started to actively ignore their requests because they weren't presented in a reasonable way...and the presenters were the *client*.

Cut off changes completely: You can say that changes at the last minute are not ideal, but to cut off changes completely at an event because presenters didn't meet the deadline is not going to benefit the event overall. Be prepared for changes to happen because events are a dynamic animal, subject to interjections from the world, from the audience, from the company, from the event itself. A presenter wanting to add in a slide in the morning because they heard a concern over and over again at the networking reception the night before is something that can and should happen.

DO:

Here are some things that have worked for us:

Use peer pressure: We worked with a client who used a peer-review session deadline; a week before the event, every presenter would get together in a room and present their content for the event to each other. They would then get presentation feedback. This forced presenters to get the content done--they didn't want to be the only one who hadn't done their part, or let down their other peers. Even having an updated list of who has/hasn't turned in their presentation can apply a bit of peer pressure to help move deadlines along.

Utilize rehearsals: The previous example not only utilized peer pressure, but it also included another component: rehearsals. Often times we like to do a "dry run" of an event a week before--even if it's over the phone. Scheduling ample rehearsal time on-site (and clearing a presenter's schedule of on-site obligations so they can attend) will also minimize VERY last minute changes.

Provide Incentives: In a particular company, presenters got $50 if they turned in their presentations on time. It's not that $50 was so much money, but it provided a tangible incentive to be on-time--and everyone in the procrastination-prone company turned everything in on time. One can also take the stick approach--meet deadlines or get time taken away--but the carrot is more diplomatic.

Shape the event and give talking points: Having a very concise theme (we're not talking "A year to win" or similar event themes, but rather a content throughline) and talking points that you'd like each presenter to hit can help them get a head start on their presentation. It gives them something to react to instead of having to generate a presentation from scratch (which can frequently hold up initial deadlines).

An example of this might be (roughly):

Theme: Everything about this event is geared toward helping the sales force get their "swagger" back after a tough few years.

Direction for presenter: How will the marketing strategy for this year help the audience feel like they have swagger? What specific things are you doing to support them?

Frame the value: Face to face events are a huge opportunity for a presenter to get in front of their audience. They are also a huge opportunity for a company to give the attendees a unified message. The importance and impact are so great that a last-minute presentation is most likely not going to cut it. Events are an investment. Framing the value of the event to presenters may seem like common sense or something that they already know (or should know), but often times no one frames it like this. Letting presenters know that this is their time to shine and step up, and communicating what it means to them and the company can help them to be more thoughtful about their presentation and attendant timelines.

--

Good event production teams are flexible and pros at making last-minute changes look effortless and flawless. That doesn't mean they *are* effortless.

Good production teams may be able to get presenters to turn in their content well before an event, but they are also equipped to handle situations in which this does not happen. This may mean extra on-site staffing, people dedicated to working exclusively with particular presenters, etc. If a production team has worked with a company before and it's been an issue at previous events, building in extra staff in the contract and citing past experience is in the client's best interest and in the interest of the sanity of the production team as well.

Role Play Roulette

Are you making enough time to prepare for your event?

Companies don't like to throw money away. Getting everyone together can be an extremely good investment...one that you don't want to squander with half-baked messaging.

Do audience research beforehand to gage the tone and mood--particularly if there are issues that need to be addressed, and even if you think you already know what these issues are.

Make presenters accountable to each other to finish and/or make progress on their presentation drafts. You can even schedule update calls with clear review objectives.

Don't let the first opportunity for feedback occur on-site. We recently had a client who was putting together an event and each presentation required input from multiple departments. The marketing team had re-branded, the sales team didn't have consistent messaging with the marketing team, and no one was very clear on what they should actually be saying. This made on-site review a mess in the past. Getting everyone physically together in a room beforehand provided a much more supportive environment for feedback and message cohesion.

We recently dealt with a client where we offered $100 to every person who had their presentation done when they were due. It's not that $100 is such a huge incentive for executives, but it gave a concrete goal to shoot for and engaged them with a competitive/motivating element.

Clear key presenters' calendars on-site, even if it means coming in a day or more early. Even if it means rehearsing on paper/face to face instead of on stage. If coming on-site early is cost-prohibitive, hold rehearsals via conference call.

How to keep your presenters on-time in 3 simple steps.

Aside from making throat-cutting "END NOW" motions from the back of the ballroom, how do you make sure your presenter stays within their allotted time?

Here are three ways:

1. Ask them how much time they need, don't tell them how much time they have.

This is during the initial planning phase--obviously you have to set some time limits, presenters who want 50 minutes may not be able to have it within the constraints of the event.

However, telling a presenter they have 45 minutes is going to cause them to fill the 45 minutes (plus some)...even if they only have 20 minutes of content. Ask your presenter how much time they NEED to do their presentation. They may only have 10 minutes--and may only need 10 minutes--and giving you their needed time helps keep them accountable for their own presentation.

2. Help focus their presentation.

A lot of presentations are done independently without a broader insight into the meeting as a whole. Helping presenters to focus their presentation--whether they're professional or internal--both keeps them to the message AND keeps them on time. For instance, if your motivational speaker is used to giving presentations to sales audiences--and your audience is full of computer programmers--not only might some of their messages/anecdotes be off target, but they may contribute to them going long.

Internal speakers may allow you to have a bit more control in working with the content. Remind them of the limits of the working memory--the average adult attention span is 5-7 minutes unless the content is presented in a new or novel way. The more important their information, the more important it is to keep the presentation short and focused. Otherwise all the addendums and additions will be lost on the audience...and will actually detract from the message as a whole.

3. Get them off the stage.

Almost every event producer has experience with speaker-timer-blindness. It's that not-so-rare phenomenon where speakers SEE the speaker timer flashing that their time is up, but they blatantly ignore it. "Just 5 more minutes" for every speaker leads to missing needed breaks, cutting into important networking time, and even throwing off schedules for group activities.

So how do you give your presenters the hook without looking like the bad guy? Warn them in advance--and let the audience know--that if presenters go over they'll be interrupted. Getting permission to do this at the beginning of the event--for all presenters--makes it a friendly (and sometimes humorous) tactic. It also lets the audience know that you and the presenters respect their time.

For instance, we were at a show where each presenter had 7-15 minutes to speak. Presentations were slotted into the agenda with precision timing--there wasn't room for presenters to even go 30 seconds over their time because it would all add up. At the beginning of the event, we had our co-emcee (an AniMated parrot character) state that if anyone went over time he would be the birdie on their shoulder--popping up to escort them gently off the stage. ONE presenter went over-time (and was escorted promptly off stage, to the delight of the audience and presenter), but there were no other time transgressions (unheard of at this particular event).

A Story of Persuasion and the Gunning Fog Index

We've also talked about the Psychology of Persuasion in the past: The long and short of it being--people are persuaded in different ways (social proof, data, experience, etc.) so one specific style of argument won't necessarily sway everyone in your audience.

This is the tale of a client, a presentation, a Wharton MBA, and how we used the Gunning Fog Index to make a case for simplicity.

Several years ago, we were helping a client (a major international Fortune-50 hospitality company) with their executive presentations. The presentations were written out and would be read off a TelePrompTer. Each executive wrote their own presentation and our job was to vet each one, suggest improvements, etc. One particular client was the VP of marketing.

She was delivering her marketing plans for the year at their annual event. Since they were going in a new direction the material was going to be very relevant for the audience (made up of Hotel Managers with only a cursory understanding of marketing and marketing terminology).

The first draft she gave us was a highly detailed examination of their marketing plan. It was well written...

... if it had been designed to appear in the Harvard Business Review.

But it didn't hit the mark for the audience. It was full of jargon, and was designed for READING not for spoken comprehension. (The brain can process reading material more rapidly than spoken material--we read faster than we can speak.) We've seen our share of presentations and are pretty savvy at understanding marketing speak and strategy--but even we had to re-read the presentation several times before we fully understood the gist of the material. Clearly there needed to be a re-write.

We highlighted key areas that should be simplified (the document had more yellow than white) and returned it. The second draft was slightly better--but only slightly. Some of the jargon was removed but it was still thick with content, huge words, and complex strategies (and sentences). It was a challenge to read and it was going to be a bear to listen to.

We sat down and had a heart-to-heart discussion with the client, but she didn't seem to grasp the need for simplicity. She stated: "Well, this is awfully clear to me... I think we're okay... I really do."

We were discussing the issue with her administrative assistant, who empathized with our plight, and she was also trying to help her boss "see the light".

Clearly, the way we were presenting our feedback wasn't persuading her. We asked her admin to tell us more about her. She explained that her boss is very bright (MBA from Wharton), very passionate about her job (that was evident in her presentation), and that she is very statistics-oriented. Statistics helped drive her decision making. Looking at her presentation, you could tell this was true. There was an abundance of data and charts. Clearly, numbers ruled for her.

Ah-ha! That's when the light bulb went on for us. We needed a way to communicate how her complex presentation was making it difficult for the audience to understand her message.

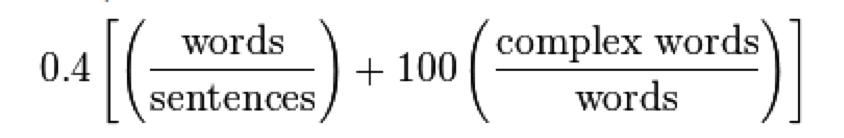

Enter the Gunning Fog Index. For someone statistically-minded, it the simple tool (and equation) used to illustrate how difficult her speech actually was to understand helped her overcome her own familiarity with the topic and look at the presentation with more objective eyes.

For the record, her first REVISED draft was so high on the Gunning Fog Index that it was at the comprehension level of a 4th year COLLEGE student--not at the level of a 7th or 8th grade HIGH SCHOOL student, like it needed to be.

By presenting her with a way to measure the result she was able to simplify the presentation and communicated the key points in a very clear manner.

7 ways to find your presentation story.

Stories engage the brain and make a message more relatable. As you tell your story the audience naturally pictures the events in their mind, creating rich detail and making memories.

It isn't always clear to a presenter, however, what story they should tell or how to find a story that's compelling. A story supplementing a presentation should be:

- On-topic: It should somehow support the message at-hand, if only tangentially.

- Engaging and relatable: It should have universal appeal to your audience. Even if it involves something they may not have experienced, the theme of the story should be something everyone can relate to.

- Evocative and emotional: The story should captivate the audience and resonate on an emotional level.

- Short and concise: Just the facts ma'am. Leave the long tangents and embellishments to Uncle Joe at Thanksgiving. Don't take too long to get to the point.

- No inside jokes (unless ALL the audience is in on the joke): There shouldn't be anything missing from the story that needs to be there. If a stranger wouldn't "get it", assume your audience wouldn't either.

- True...or not: A story doesn't have to be *completely* true, it just has to have the ring of truth. Obviously you shouldn't make up facts/figures, but adding a little embellishment is no presentation sin.

There is always a compelling story *somewhere*. Here are a few ways to discover stories for your own presentation.

1. Your life:

So you haven't climbed Mount Everest. That doesn't mean that you don't have compelling anecdotes from your life.

Visit your childhood experiences. Were you ever on a team? Do you have siblings? Did you go on family vacations? What about your own kids (if you have them) or friend's kids? Have you traveled? What about college? Did you have a wedding? Think of the significant emotional events in your life, and there are bound to be one or two nuggets that can be tied into your message.

2. The process of creating the presentation:

Creating a presentation can be a story in and of itself, as long as it doesn't get too navel-gazey. Did you expect to have to do this presentation? Was it difficult to put together? Did you discover any surprising things along the way?

Assembling your PowerPoint slides on the airplane on the way to the conference isn't much of a story, but it can be a jumping-off point to more insightful commentary. "As I was sitting there on the plane, wondering what the heck I was going to talk about and trying to ignore the thin trail of drool on my shoulder coming from the stranger in the middle seat, I realized..."

3. From pictures:

If you're stuck for inspiration try looking at pictures--from your life, from past events, or from the great wide world. A story doesn't *have* to be true--some of the best stories are fables. Speculating as to what's going on in a compelling picture, or creating a metaphor based on an image and tying it back to your message is a good shortcut to a story.

Perhaps a picture of the company's founders will inspire an origin story that dovetails nicely with the current goals of the coming year. Vintage photos, kids, animals, evocative imagery--all of these things can be good jumping-off points.

4. An origin story:

A story is basically who-what-when-where-why-how. We had a client revealing their new marketing plan to their retail sales managers. Instead of just giving the plan, they told the story of how it came to be; how they were inspired by visiting the factory and that informed the direction of the plan. Not only was it engaging, but it gave a richer picture of the marketing materials at-hand.

How did a new product come to be? What trials and tribulations were overcome? How did you develop the new sales plan? What informed the decision? What happened last year that is making what you're saying this year relevant?

5. Plum the sports world:

Sporting events and personalities have natural arcs of triumph and trial, success and downfall, drama and delivery. Sports anecdotes are very popular in presentations, but there's a reason for that; they're naturally evocative.

Not all people can relate to sports (or a particular sport), but most can relate to a struggle against overwhelming adversity, not giving up during harsh conditions, or beating the competition against all odds.

6. Famous figures:

Like sports figures, famous writers, personalities, actors, musicians etc. often have strange and compelling stories because they are often thrust into strange and worldly situations that create anecdotes. Picking familiar figures and tying in their story/anecdote to your point can create a moment of humor and engagement.

One speaker we heard tied the company's message of teamwork and making risky decisions to the origin of The Beatles, for instance.

|

| Why doesn't that third Beatle look familiar? |

When all else fails, the internet is a practical repository of stories. Anecdotes, metaphors and experiences abound and are shared freely. It's not difficult to find an interesting story online after searching some keywords that relate to your message.

Here's where you do have to measure the truth, however. Not everything on the internet is factual (gasp!) and while it's fine to use fables, don't present a false story as the truth--always fact-check! Snopes.com is a good place to start if an internet story seems just a bit too convenient and fantastic to be true and you want to sniff out its authenticity.

Engage: 8 Ways to Recapture Your Audience

The Five Perils of a Panel

Indeed, panel discussions at places like ComicCon and similar are exceedingly popular and very interesting to their super-fans. The key there being super-fans.

How about when you have a sales audience and you have a panel of customers?

A panel of executives presenting to the rank and file?

This is an entirely different story. These panels often come off as flat, unengaging and boring. When you look at the best aspects of a great presentation, these elements seem to be missing in panels entirely. So why are these panels so painful and deadly-dull for the audience? Where do panels go wrong?

1. They're usually not needed and have unclear outcomes.

Typically people come up with the idea to do a panel because they think it will be more interesting than a series of presentations. That may be the case, but doing a panel for the sake of doing a panel doesn't produce the results one desires. Panels are not exempt from needing explicit, clear and focused outcomes. Without an outcome, the panel can wander, lose focus or suffer from a lack of focus to begin with.

2. The dynamics of a panel often fall flat.

What is intended to be a differentiated format often offers no differentiation of its own within itself. There is no emotional charge behind a panel. They suffer from a lack of narrative drive, and there is no cohesive story to captivate and intrigue the audience. Often times the presenters lack chemistry or relation to each other, so even the format of the panel cannot be used correctly.

3. Panel presenters have a broad spectrum of ability.

Some panel members may be very engaging and others may not. This would seem to be fine, but often those that aren't engaging or may not even have much to say about a topic at hand feel obligated to jump in on a topic to fulfill their panel time or justify their presence on the panel. Instead of hearing from an expert in a cohesive way, the audience may hear from several non-experts in a disjointed way. With uneven presentation skills, the audience comes away with the experience provided by the lowest common denominator.

4. Panels give a lack of control over presentations.

Panels--especially those featuring gracious customers or outside volunteers--offer very little control over the messaging and storyline. It's easy, within a panel discussion, to veer off-topic or into taboo territory. Presenters may grandstand or focus on what they find interesting about a topic versus what the audience needs to know or what the audience finds interesting.

5. Audience questions fizzle out in a panel.

This is not a problem unique to panels, but it can be amplified by the panel format. In order to incorporate audience interaction, panels often will solicit questions from the audience. The audience will then typically ask what is most important to them personally...and it may have absolutely zero relevance to anyone else in the room. Generally audiences are not great at moderating their question level to the broader interest of the group at large. In a panel, then, you may have a question come up with little relevance, but that ends up taking up a large chunk of the panel time.

Panels aren't all bad--don't get us wrong--it's just that they are so often misused and abused. So how does one go about fixing panel perils? Our next blog installment will cover what you can do to make a panel more effective.

Important Message + Humor = Engaging Message Delivery

But this messaging is VERY important and could save a passenger's life in the event of an emergency. So what's an airline to do? Add in humor.

Delta put out two new safety videos:

Version 1:

Version 2:

The thing that's so strikingly good about these videos? They take their message seriously but they don't take themselves seriously. They know that people are tuning them out, but their message is critical, so they add moments of novelty and absurdity. These little "bonus" additions give the viewer something to focus on. It refreshes their attention and makes them look forward to the next moment of novelty or delight.

We hear a lot of companies say that their message is SO important that to have fun with it would diminish its seriousness. Well, what's more important than safety information in the event of a life-threatening situation? The fun doesn't diminish the message. The point is this: No matter how serious your subject, if your audience is tuning it out, it isn't going to be heard and remembered. Therefore it pays to have a little fun with it.

We here at Live Spark have flown hundreds and thousands of times. We've HEARD these pre-flight messages before. And yet we all watched these videos all the way through...twice.

Presentation Pet-Peeves

However, there are a few fairly frequent mistakes that speakers make that tend to negate the good will of their audience. After hearing a few hundred (probably closer to a few thousand) speakers--both internal and external--these are our biggest presentation pet-peeves.

1. Apologizing for their time.

"I know it's been a long day, try to stay awake..." or "I know I'm coming between you and lunch..." Sometimes this comes off well--with a strong speaker--as a lighthearted attempt at humor. More often it comes off as a reminder that I really want to check-out and a red-flag that this speaker doesn't consider him/herself important enough to listen to on their own merits.

Instead: Own your time. What you have to say is important. If it's not, don't be on that stage. The audiences' time is a gift; don't apologize for taking it--make them glad that they gave you their time because you're giving them something valuable in return.

2. Saying "in conclusion" and not really meaning it.

I once heard a speaker--no exaggeration--declare his conclusion a half-dozen times in his presentation. He may have meant to conclude single points among many in a fairly long speech, but there was no way for the audience to know that. He said, "In conclusion..." and everyone prepared for a summary statement and the end. The fact that he then went on another 5 minutes, then concluded again, then went on another 10 minutes, and then concluded again, and so on and so forth, sorely tried the patience and attention spans of the audience. By the time his real conclusion came about a more fidgety bunch of folks I have never seen.

Instead: Only conclude when it's time to end your speech. You have 30-60 seconds to wrap up after you make a conclusion statement. It's a great signal in a presentation to have the audience sit forward and take in your final point, but they don't appreciate being jerked around by multiple conclusions.

3. Using incorrect/outdated/inaccurate information.

We were listening to a speaker who was giving a professional, paid presentation on a very serious topic. To make a point via metaphor, she told a story about a military dog--Brutus--who protected his captured owners by killing their captors with a single silent signal. Something about the story wasn't jiving, so those of us with smartphones (a great majority by now) went on a little fact-finding mission at Snopes.com. The story turned out to be untrue and debunked. Not only did we spend time in her presentation checking this out instead of listening to her message--but she lost some amount of credibility in her actual message.

Instead: Use metaphors that you know to be true, and fact-check any anecdotes, datapoints or tidbits of information. If your aunt forwarded you the email that you got the story from, it's best not to just run with it in your public presentation.

4. Thinking your message is more important than it is.

Being unable to see the relevance of their message in perspective to the audience's perception of its relevance is a huge stumbling block for a lot of presenters. Sure, you've spent 11 months in the trenches of marketing and the minutia of the new PR rollout is really fascinating for you and your team and you're really proud of it... but does your audience feel that way too?

It's like the episode of Seinfeld where Jerry and Elaine go to visit their friends who just had a baby. Their friends, of course, think their child is the most beautiful thing in the world...but...it's an ugly baby. Your content is the baby. You may think it's beautiful but it might not be completely relevant to your audience.

Instead: Think about the perspective of your audience before crafting a presentation. Does it fit into what they immediately NEED to know? Does it fill in a "what's in it for them"? If not at all--or you can't think of a way to make it relevant/fit--then you may not be the right choice for a presentation at that event.

5. Not rehearsing

You'd think that if someone were presenting in front of a group of thousands, they would at least rehearse their presentation, right? Wrong. And it shows. Sometimes this is as simple as not testing the technology--the video clips, the PowerPoint, the transitions, etc. Other times it's as simple as not practicing and being rough, unpolished and nervous. Still other times this manifests itself as speakers going way, way, way over time.

Instead: Even the best speakers in the world practice each presentation. Test your technology. Make sure your timing is right. However, do NOT rehearse by memorizing your speech. Be comfortable enough with your talking points to relax and simply talk TO your information instead of repeating back the information.

6. Having a very obvious "insert company here" message.

This is more for professional external speakers that make the rounds at big corporate events. A lot of speakers have a fairly canned message about how they accomplished X and Y and how it's relevant to you, as an employee of Z company, accomplishing A and B. Sometimes you can literally hear the pause for the "insert company here" line in their speech. Is it really relevant to that company? Does the speaker actually know anything about the situation? Not really. Yet they're trying to be motivational with a generic message.

Instead: Good keynote speakers take the time to get to know the situation in the company and customize their message accordingly. They may have a bank of several messages or key points they can draw from or put together depending on the needs of the audience in front of them.

Your Audience Has Baggage

It's all pretty straight forward; but is the message that is being delivered even acknowledging the state of the audience? People don't just come into a sales meeting all tabula rasa; waiting for you to dump 8 hours of information into their heads (not that information should be dumped anyway, but that's another blog post). They come with the whole year on their shoulders.

We're not saying that you have to start off a meeting with a little therapy session, but measures must be taken to move your audience from baggage-carrying and not-really-listening to an unburdened audience ready to see the possibilities of the next year. If you don't do this, every persuasive point you try to make (i.e. "We can hit 3% growth, here's what I want you to do," will be met with skepticism).

1. Acknowledge what they're going through. If it's been a tough year, don't kick off the meeting like everything is great. Ignoring a major communal issue that the audience has isn't going to make them forget it--it's going to make them reiterate that issue in their heads after every point you make.

It's not enough to say, "It's been a tough year," either. Open by relating to the audience. "I know it's been a tough year; you've had problems retaining sales leaders, our clients only seem to want bargains, we're late on x product." That way you can get over the past and move forward into the coming year. Maybe the situation isn't going to improve--but acknowledging that you're all going through it is going to help people deal with it as a team.

2. Anticipate objections. You want the audience to adopt a new sales strategy, but in the past you've gone through "new sales strategies" like a couch potato working on a bag of chips? (This year: Relationship Selling! Next year: No, Now Whiteboarding!) What makes you think that the audience will have faith that the new way will stick around? Why would they make the effort to adopt something that will be gone in a few months? Pre-frame their objections by acknowledging the situation of the past and giving concrete reasons (what's in it for them) for the future strategy.

3. Acknowledge your shortcomings. If you didn't deliver on something--don't be afraid to admit it to your audience. "We know that we didn't give you marketing support like we promised, but we'll have to do more with less." It's not justification to tell the story of an initiative gone wrong. It's a way of bringing it to a rational, understandable level. Be sure to follow up, of course, with why it's not going to be this way in the future (or alternate options if it IS going to be this way in the future).

4. It's not all negative. If your team busted their behinds all year and did a great job, don't start off by telling them how much more they're expected to grow in the coming year. It's okay to celebrate. This doesn't mean that you'll be resting on your laurels in the future, but many people are driven by significance and positive reinforcement. Be sure to give your team the props they deserve for a job well done.

The Anti-PowerPoint Movement

It's rather popular to openly, vocally dislike PowerPoint. It's almost cliche to groan when thinking about a presenter with slide after slide after slide of information. By now, most people have heard the expression "Death by PowerPoint" and have seen PowerPoint presentations that make getting a root canal seem like it'd be a grand way to spend a few hours.

It's rather popular to openly, vocally dislike PowerPoint. It's almost cliche to groan when thinking about a presenter with slide after slide after slide of information. By now, most people have heard the expression "Death by PowerPoint" and have seen PowerPoint presentations that make getting a root canal seem like it'd be a grand way to spend a few hours.

It's a bit unfair; PowerPoint is a tool and is not directly responsible for its misuse. However, when the misuse is so rampant and there seems to--generally--be little interest or ability to create different, fresh and truly effective PPT presentations, it's natural that people would grasp on to available alternatives.

But...are we throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

We saw this article on Yahoo! News and we have thoughts. Our commentary is in bold-italic.

10 Things to Do Instead of PowerPoint

The bad news: there are thousands of presentations every day, everywhere around the world. Most of them use PowerPoint, badly, as speaker notes, with more words or numbers on each slide than anyone can read.

The results are predictably boring – no, excruciating -- for their hapless audiences. That’s human misery on a massive scale.

The good news: in an effort to make the world a better place, here are 10 things to do instead of PowerPoint. Ways to make your points without the sleep-apnea-inducing effects of boring slides. Ways to pep up your presentations without much additional effort. Your audiences will thank me.

1. Use props. For most workers, in a cubicle world, it’s sensory deprivation from 9 – 5. The whirr of computers and the A/C. The hum of colleagues chattering away. The beige walls of the cube farm. The fluorescent lighting. It’s amazing anyone stays awake. Offer the audience, then, something physical. Instead of describing that new product on a slide, show them a prototype. Pass it around. Let the audience get physical.

Workers can also be out in the field every day and absolutely unaccustomed to sitting still in a presentation for x hours. There are people who learn by seeing and hearing, but there are also those who learn exclusively by doing. Many people would prefer to DO instead of SEE: Think of someone who doesn't read directions before trying to put together a piece of furniture...even if they don't get the best results.

2. Use music. We have an emotional response to music which is much more powerful than we do to most words. Especially words like “3rd Q results” and “product optimization.” So add a soundtrack to your presentation. It will bring it to life. Do obey copyright and licensing laws, please.

Music can, in our experience, be a tricky thing within a presentation--simply because evoking that emotional response should be done with care. Choose the wrong piece of music and it's discordant. Ahhem. Also make sure that the music is unobtrusive--or you'll get a jam session instead of a content session.

Music should also be used throughout an event--not just in a presentation.

3. Use video. Video –good video -- has all the life in it that static slides lack. A good clip can enchant, move, and thrill and audience in 60 seconds. You can create the right emotional atmosphere to begin or end a speech – or to pick it up in the middle.

Or use a bad video. Not a boring video, but a low-quality, as-seen-on-YouTube video that entertains and delights. Use video to tell your story. Use video to evoke an emotional response. Use video to demonstrate a product. The key is to entertain with the video (humor is very effective) and to keep the video short.

4. Use a flip chart. Create any visuals you need right there in front of the audience. No need for technology. Just a magic marker and your arm. The act of creation draws the audience in where a slide doesn’t.

Your results may vary. We've had mixed experiences with flip chart presentations. While some supplement is very effective; your short-hand is not always the short-hand of the audience, flip charts can be hard to read, and presenters vary greatly in artistic/calligraphic ability.

5. Ask the audience. Of course, the best way to draw the audience in is to draw them in. Ask them to tell you their stories – as they relate to the topic at hand. Ask the whole audience or just selected volunteers.

Pre-screen these first. WARN someone that they'll be asked to tell an anecdote if you can--or you better know your audience very well. Never put anyone on the spot unprepared, and make sure that the selected audience member has a concise, cohesive, relevant-to-everybody story to share. We've seen audience anecdotes that were more dull than a bad presenter.

Beware the crickets chirping. It may take away from the spontaneity of the interaction, but be sure that you have someone who IS ready to share.

6. Ask the audience – 2. Break the audience up into small groups and get them to respond to a challenge that you set, a question that you ask, or a problem that you pose. Then have them to report back to the whole group.

This is a great idea. Discussion groups allow people to make information personally relevant and sharing with peers reinforces content. Set acoustic conversation music in the background and allow tables to discuss for several minutes. Designate a team leader who will be charged with collecting responses and reporting back.

7. Ask the audience – 3. Play a game with the audience – relevant to the topic. Award prizes. Audiences love to compete. Just don’t make the questions too difficult or the prizes too expensive – or too cheap. Only Oprah gets to give away cars.

We couldn't have said it better ourselves. Games are a fantastic way to engage the audience. Have a game that runs throughout the session, opens the session, or reviews content at the end. Put the audience onto teams and keep them in teams.

8. Ask the audience – 4. Get the audience to design something – new products, plans, or ideas. Give them plenty of paper, sticky notes, ipads, or whatever you have on hand that they can play with.

Adults want to play, too. Giving the audience a chance to exercise their creativity allows their brain a natural "break" to absorb and synthesize previously covered information. Content-related creativity can be extremely fun and actually inspiring.

9. Ask the audience – 5. Have the audience create video responses to what you’re talking about. Hand out a dozen flip cams and get them in groups. Give them a limited amount of time – 10 minutes, perhaps. Then show some of the video to the whole group on the big IMEG screen.

This is a wonderful idea in theory. In practice we've learned that most people aren't even amateur videographers. While the act of creation is fun, it's tough to get everyone involved, tougher to shoot something that is engaging to watch, and toughest still to organize it in a brief amount of time. That's not to say it can't be done--and we have seen some incredible audience-created video pieces--but use with caution.

10. Combine any 3 of these to create huge audience buzz. Stop thinking of a presentation as a static activity where you show slides to a catatonic group of fellow humans. You passive, them active. Instead, treat them as co-conspirators in something exciting, educational, and fun.People learn best when they can make the information relevant to them. This includes synthesizing it in a variety of ways; quiet reflection, group discussion, personal practice, hands-on activities and even creative, fun exercises. The enemy here is not PowerPoint, it's a lack of consideration for an audience that wants to actually INTERACT instead of be talked to for hours in a way that is disrespectful to the workings of the brain.

Presenters Like Presentations That Are Fun To Present

Here's a novel concept: a dense deck of PowerPoint slides is just as not-fun for the presenter as it is for the audience.

Here's a novel concept: a dense deck of PowerPoint slides is just as not-fun for the presenter as it is for the audience.I guess we've always known this is true in the back of our minds; but if a presentation wasn't fun to present, why would a presenter present it? (Ladies and gentleman, your new tongue-twister.)

We stumbled upon this revelation (ehhem) when consulting with a client about their lunch-and-learn style presentations. They wanted a fun, brain-based presentation that was turnkey; anyone presenting could give a good, engaging presentation--even if they weren't their top choice for a speaker. Then our client said, "Well, if we have a fun presentation, it could make the presenter better. After all, presenters like presentations that are fun to present."

The lightbulb went on!

We're so entrenched in advocating for the audience to be engaged, that we forget that a speaker can become a talking zombie; someone who is just delivering the words and going through the motions without enjoying the experience. The presenters' enjoyment always took a backseat to the audience--and we went forth crafting energizing, brain-based presentations without being aware of the effect it had on the presenter.

It's true, there are some presenters who can make a proverbial silk purse out of a sow's ear--taking a 49 slide deck with 18 bullet points per slide and presenting it in an energetic way. . . but they typically aren't just *presenting*, they're also engaging with jokes and anecdotes and going off the slides, etc. If you had to substitute speakers at the last moment, giving that same presentation wouldn't be nearly as agreeable.

Just as the audience doesn't want to listen to a speaker just reading slide after slide, we can't imagine that that's what speakers want either. Not only does it not provide a creative outlet for them, but not having a presentation that engages the audience deprives a speaker of the critical positive audience feedback--the effervescent bubbling of energy in the room that you feel on stage when you're really *on* and they're really liking what you're saying.

So I guess the point is a humanitarian one: don't just improve your presentations for the sake of the audience, do it for the presenters, too.

Why we Love Steve Jobs

We love Steve Jobs from Apple. Well, I mean, we don't personally love Steve Jobs, but we do love the way he presents.

We love Steve Jobs from Apple. Well, I mean, we don't personally love Steve Jobs, but we do love the way he presents.Our office gathered around a laptop (yes, a Mac) to watch Mr. Jobs announce new iTunes, Apple TV, and iPod Touch (among other) upgrades. As we listened to him speak, it became abundantly clear that he's a walking best practice for presentations.

Not that this is revolutionary, much has been made at websites like Presentation Zen, etc. about the clean, clear way that Mr. Jobs presents.

He:

Has clean slides with lots of "white" space.

Has clean slides with lots of "white" space.His slides are so simple, in fact, that the average presenter would be tempted to add just a bit more. A few talking points, perhaps? Alas, the simplicity is crucial. The slides are easy to understand, impactful and resonate INSTANTLY with the audience.

He is a great technical speaker.

There's a lot of training that goes into a speaker being seen as "down to earth". It's a hallmark of practice that Mr. Jobs presents with such ease, and so that everyone--from your average at-home blogger, to a shareholder, to a technician, to the consumer--can understand the message. Not only is his message colloquially phrased, but he has genuine passion evident in his speaking. Rehearsed/fabricated (we think not) or not, it makes the presentation that much more compelling.

Has a great process for learning.

Mr. Jobs presents the features/benefits of his product, then he demonstrates how it works, then he recaps the features and benefits. Not only does this change the way the information is presented--making it more engaging--but it also reinforces the learning. He'll take out a product and demonstrate the physical process of a procedure on stage. This connects all the dots--from features to function.

Whether you're an Apple user or not, there's no denying that Steve Jobs does one heck of a job presenting his products. It's a style we could all afford to emulate in internal OR external presentations.

Cartoons in the Senate

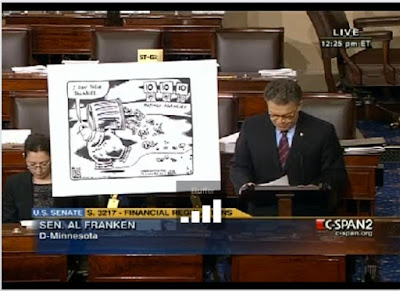

The internet is somewhat up in arms about what is seen in the image above--Senator Al Franken using a political cartoon to illustrate a point during a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate. The editorial cartoon pointed out a problem with an existing financial bill that Senator Franken's proposed bill will solve.

The internet is somewhat up in arms about what is seen in the image above--Senator Al Franken using a political cartoon to illustrate a point during a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate. The editorial cartoon pointed out a problem with an existing financial bill that Senator Franken's proposed bill will solve.Now, we're not touching the political aspects of the cartoon, proposed bill or Al Franken. What we *would* like to comment on, however, is how effective the showing of the cartoon is in making a point and as a presentation tool.

True to the form of editorial cartoons, this illustrates the crux of the issue in a highly visual manner. Senator Franken was able to leverage this to make a point that the public can easily relate to. Instead of trivializing the issue by being a cartoon--it highlighted his presentation in a way that was clear and engaging.

We've seen similar cartoons make their way into keynote speeches. Besides illustrating and highlighting particular points, they also make the audience stop, laugh and pay attention. The absurdity, the humor, the visual format all combine to make them an incredibly effective tool in a presentation.

So Senator Franken used a cartoon...and now everyone's talking about his presentation. Agree or disagree with his points; one has to admit that it's rare that a run-of-the-mill, every-day Senate presentation makes much of a ripple in mainstream news media. We doubt that such a stir would have been made if he used a PowerPoint slide rife with bullet points.

An Internal Affair: The Problem With Internal Speakers

Internal speakers get a bad rap.

Internal speakers get a bad rap.Not to say that it isn't largely deserved; for the most part, internal company speakers are what one talks about when they reference such phrases as, "Death by PowerPoint" or "Information Overload" or "Podium Ambien". (Okay, so I made that last one up.)

Professional speakers--again, only for the most part--manage to avoid such pitfalls. That's not to say there aren't exceptions to the rule: I've seen fabulous internal presenters and pretty lousy professional keynote speakers. It's just that when one makes their living doing something, they tend to do it fairly well. A company probably didn't hire a CFO to give an ace 50-minute presentation once a year at a sales meeting...they probably hired them to be really, really good at company finances. So presenting really *isn't* an internal speaker's main job--they already have a job to do, and one can hardly blame them for giving a comparatively small presentation the short shift when their main focus is on their daily responsibilities.

Recently I stumbled on a discussion of event industry professionals centered around poor presenters. The general consensus was that companies should hire professional presenters to escape from the trap of sub-par internal speakers.

Well, that might work for a keynote speech, of course, but I would say that not only is this financially prohibitive on a bigger scale, but it's also unrealistic, largely unnecessary and can take away a lot from the meeting--including critical information. After all--if you need someone to give the financial picture for the company moving forward, the best person to do it is someone internally who deals with that particular facet.

I'm not that quick to brush off internal speakers all together. There are definitely ways to coax a more engaging presentation out of a non-professional speaker:

Make it an Interview. A dialog can be much more captivating than a monologue. Have an emcee or dynamic colleague ask the presenter pointed, relevant questions. Keep the conversation focused and moving along.

If one is feeling like doing something different for an event, one could even stage the general session like a talk show--keeping the same emcee to transition between different subject matter experts.

Present as a Team. The head of a department can give a brief overview, and then hand off to members of their team to present--or presenters can take turns. Not only does this change who's on stage--adding novelty and re-engaging the audience every time the presenter changes--but it can also be a great opportunity to let a team share in the "glory" and let themselves be known to the audience.

Keep it High-Level. Internal speakers are often subject matter experts that spend all of their days doing their job in the area that they are speaking about. It's great that they're passionate and knowledgeable about their subject--but it's not often that the audience shares the same level of enthusiasm. For instance--a sales force doesn't want to (or need to) know *all* the little nuances of the marketing process and department and plan--they just need to know the parts that are relevant to them and will help them most in their job. Information overload can be prevented by keeping everything very high level--the presenter should think about what's important to the audience as opposed to what's important to them.

Add Variety and Multimedia and Novelty. There's nothing more compelling than a story--and internal speakers are full of them; they just don't know it. Stories, metaphors, pictures, video clips--all these tools can be incorporated into presentations to significantly boost the engagement factor. A story doesn't have to be a personal anecdote--sometimes a presentation *does* tell a story if framed correctly. Instead of clip-art pictures, use bold, big, colorful and memorable graphics. (And take out some of the PowerPoint text while you're at it.)

Case studies are also great. A presenter doesn't have to tell the audience how program X will benefit them--give a case study. Better yet, call the case study subject on stage to interject their story during the presentation. Variety, multimedia and novelty are all key in keeping the audience off the Blackberry and on the presenter.

Have a global, pre-defined and assigned set of outcomes. Having a set of clear outcomes for an event is huge. Define outcomes and give them to presenters. If they want to talk about something, it must somehow support one of the outcomes. If it doesn't, they either cut that information, or renegotiate. Every presentation should support the event--and having a cohesive set of outcomes both within the event and within each presentation will keep everyone on-message (and prevent speaker-speech-wander). Don't be afraid to cut time when it's not needed--just because you've always allotted 90 minutes for the marketing team, doesn't mean they have 90 minutes of relevant, outcome-based content THIS year.

Rehearse. It's torture to sit through an already-dry presentation only to be confronted with technical glitches, "What happened to my slide? Can you go back one?", and unprepared speakers. Internal speakers have regular jobs within the company, so they're not always given adequate time to rehearse. This isn't just an on-site task, by the way. Reviewing their presentation as they go along with a trusted peer, team-member or assistant (anyone with an honest, knowledgeable, critical eye) can keep it on-point and fresh.

Toss the PowerPoints. Look. I've heard it hundreds of times; "Well, [CEO, CFO, CMO, VP, Etc.] is just going to do his/her slides on the plane before the event...so there's not much *we* can do about it..." Not only does this tie in with not rehearsing, but if a presenter doesn't have time to prepare in advance--cut the slides! Not only do night-before slides have infinitely more mistakes, but they're also much more likely to contain the speech instead of being a speaking aid. Consider supplementing PowerPoints with handouts, or even a recording of the presentation (or presentation notes) on a website after the event.

The Key to your Keynote Speaker

We're not in the business of brokering keynote speakers, generally. But after attending hundreds of events that use keynote speakers, we know what works and what doesn't, and can give some good recommendations. (In the events business, you know you have a great keynote speaker when the AV crew pays attention.)

We're not in the business of brokering keynote speakers, generally. But after attending hundreds of events that use keynote speakers, we know what works and what doesn't, and can give some good recommendations. (In the events business, you know you have a great keynote speaker when the AV crew pays attention.)The keynote speaker can be a critical piece of your event--they're there to motivate your audience, to tell a story and to inspire action. They should fit into your event plan seamlessly and strategically--becoming a part of your overall message instead of just a novelty.

The things that make a great keynote speaker can vary, but the things that make a bad keynote speaker are pretty much the same across the board.

Here are some things you should watch out for when looking at a keynote speaker:

1. Lack of Customization. This is the number one failing of keynote speakers. We've all heard speeches that sound practically like recordings with a space left blank to "insert company name here". Your keynote speaker should take the time to get to know YOUR message, your company's unique challenges and attributes--and be willing to tailor their speech accordingly. In the case of keynote speakers, one size does not fit all.

2. An Amazing Story...But Not Much Else. There are keynote speakers who have done genuinely amazing, awe-inspiring things...but that doesn't mean that it translates into a keynote speech. Be wary of stories that don't have a deeper message and take-away. The goal for your attendees will not be to climb Mount Everest (usually), but, rather, to overcome THEIR obstacles.

3. An Amazing Speech...But Not and Amazing Speaker. Believe it or not, there are great keynote stories and messages that get lost, quite literally, on the floor of your event. We once saw a keynote speaker who had a great message, but only his lapel got to hear it--he was just cutting his teeth on the keynote circuit, and didn't quite have the whole, you know, *speaking* thing down yet. It's critical that the keynote speaker be able to connect with your audience.

4. It's All About Them. We've seen many good speeches that have been polluted by the litter of the speaker's own ego. When every point at the end of the story or anecdote is, "You'll find this in my book," it gets tiresome for the audience. Additionally, great keynote speakers are all about the people in the room--not necessarily their own achievements. Their story should be a frame for their speech--not the entirety of the message.

5. Basic Presentation Mistakes. Most keynote speakers rank pretty highly on the professional-looking presentation spectrum compared to most internal presenters. However, they can still occasionally fall prey to mistakes like having too much on their PowerPoint (using them as speaking notes instead of visual aids, or making them hard to read). A lot of the time, companies won't proof or spend much energy on the keynote speaker's presentation--they just plug it into the master slide deck and go. That's when basic mistakes happen; a clip fails to play, the formatting becomes messed up, etc. Having rehearsal helps mitigate this, but we find that the keynote speaker doesn't always come in for rehearsal beforehand--either because they're too busy, or the company doesn't have the budget for the extra time.

Pecha Kucha in Practice

Pecha Kucha (pronounced pa-cha-chka). Is a presentation format developed by Japanese architects who wanted to show off their work, but who were sick of the same old death-by-PowerPoint presentations.

Basically, a presenter is allowed 20 slides--20 seconds per slide--for a presentation total of 6m:40sec.

At first brush, this sounded like a wonderful idea. It limits the time and presentation space that presenters have in such a way that they have to be highly selective and highly visual in order to be effective. Or they *should* have to be selective, anyway.

Then we saw our first batch of Pecha Kucha presentations at a recent event.

While the concept is still a great one, in practice it fell far short of an effective presentation style.

Why was this?

Well, the presenters treated it like just another presentation--only shorter. This meant that there was the same visual clutter on the PowerPoint slides, the same slide-as-speech mentality, and--worst of all--the limited time did not seem to have an effect on the content focus. Instead of being short, concise and witty--as we envisioned a Pecha Kucha to be--they were meandering and--at some points--a bit schizophrenic in their direction. That, and there was still the ever-present sin of trying to cram as much information as possible into the presentation (only with limited time, you can imagine how well this worked out--talk about overload!).

It goes to show you that just because a presentation is short, does not mean it's engaging. And just because it's reduced in length does not make it concise. The presentations should have been laser-focused, but instead the presenters didn't really know what to do with the format, so they reverted back to presentation-as-usual (only crammed into 6 minutes and 40 seconds).

We're not saying it's their fault--most people are raised in business culture to think of presentations in one way; the way they've always been done and the way they always will be done--damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!

So perhaps we just need to refine the Pecha Kucha in order to make it a more effective presentation tool...

...or perhaps we still need to look at presentations differently. Not as vehicles for information delivery, but as vehicles of communication. More on that later.

A little bit of Funny...

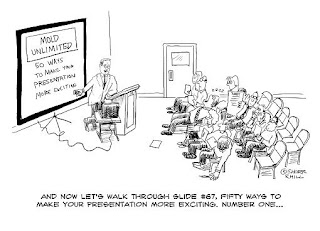

We thought this was too funny not to share:

Wow Factor Added to Corporate Presentation

It makes us think about what *really* adds a "wow factor" to a presentation...interaction, simplicity, engagement, stories...perhaps not just the bullet points. :)

PowerPoint Pecha Kucha

"Then they'll do their Pecha Kucha presentations," said one of the creative directors.

The what now?

Pecha Kucha (pronounced pa-cha-chka). It's a presentation format developed by Japanese architects who wanted to show off their work, but who were sick of the same old death-by-PowerPoint presentations.

Basically, a presenter is allowed 20 slides--20 seconds per slide--for a presentation total of 6m:40sec.

We kind of love the idea.

Obviously, it's not going to work for all content and all presentations, but the concept is great.

- Because there are only 20 seconds alotted per slide, slides have to be very graphically heavy.

- Simplicity is key--there are no eye-chart graphs, because you can't absorb that in 20 seconds.

- The rapid-fire format is a break from the norm, and has the potential to be incredibly engaging.

- There's something *different* and catchy every 20 seconds, continually reinaging the brain.

- It forces presenters to pare down their information into the most critical bits.

AllPlay Web: Curing the Common Webinar

Live Spark has redesigned a lot of events over the years. When the economy started turning down, however, events followed; a result of travel budgets decreasing on a great scale.

Not to worry, however. Live Spark doesn't really specialize in *events* exclusively (though we make a huge impact in that space). No, what we've always been concerned about is presentation; finding ways to communicate information in a more efficient, interactive, effective way, ensuring that MORE of the crucial points are retained by the intended audience.

So when live, face-to-face events started being supplemented or replaced by webinars--or web conferencing--we found a niche where we could also make a difference. After all--what is a webinar but a presentation?

What we found was that a lot of webinar hosts were making the same mistakes in a webinar as they were in their face-to-face presentations. There was PowerPoint--and how!--very little interaction, and no call to action, review or accountability.

But a webinar--more than anything--cannot be a presentation as usual. Attendees aren't in an event space--eyes dutifully turned towards the stage and away from their Blackberries because they hold a sense of obligation to look like they're paying attention. They're in front of their own computers with the great, powerful and endlessly diverting internet in front of them. With email! And games! And... well, one gets the idea. There is no way to ensure that they're paying attention.

The need to engage webinar attendees is greater than ever. They need interaction. They need accountability. They need measurability. They need feedback. They need camraderie. They need...competition and fun and engagement and...and... and....

They need AllPlay Web.

Developed by Live Spark's sister company--LearningWare--AllPlay Web allows you to engage every webinar attendee with an online game show experience.

· Each webinar attendee participates using their own onscreen keypad.

· Individual player results are tracked for accountability and analysis.

· Works with every Webinar provider: Webex, Gotomeeting, Elluminate, etc.

It's a great resource that we've begun to utilize in re-designing our client's webinars to be brain-based, interactive and anything BUT a presentation as usual.

If you’re conducting webinars, you must check this out.

Watch a video here:

Or go to www.learningware.com and sign up for a webinar to see it in action.

The Seven Truths... Truth #4

Exploring the fourth truth in Live Spark's The Seven Truths About Events (that you may not want to know).

Exploring the fourth truth in Live Spark's The Seven Truths About Events (that you may not want to know).Truth #4: Studies have shown that people generally only remember the opening and closing parts of any given presentation.

Considering most presentations, this may be the scariest truth of all. If you think about most speakers—the most important information is generally put in the middle (where it is henceforth forgotten). This is why we call it the "Jan Brady Effect"--poor Jan; the Brady Bunch always made time for and remembered and paid attention to Cindy and Marcia (Marcia! Marcia! Marcia!), but as the middle child, she was forgotten.

How does this relate to your event? You want people to remember the meat of the content--usually placed in the middle of a traditional presentation. The frivolous warm-up joke and wind-down anecdote usually fall to the bookends--where people are paying the most attention. Therefore presentations need to be structured differently—rearranging the content so that the most important things fit in where they’re most likely to be remembered.

So, how do you ensure that they remember poor Jan...errr...your most important content? Here are some steps you can take to negate the Jan Brady Effect:

1. Outline the key points for the presentation in the beginning and the end.

Say it once, say it twice, say it three times.

Highlight your key points in the beginning. This both prepares a learner's mind for more in-depth content, and it introduces the topics once. Keep it high-level and simple, but very relevant.

Go in deeper in the middle. The meat of a presentation is a great place for depth and detail. Not all details may be remembered, but the content will be closer to sticking.

Recap at the end. The end of the presentation--after the "in conclusion" should be a highlight of the most important, most actionable, most relevant key points. This is what you want the audience to act on, and what you really want them to take home.

2. Pepper different presentation elements; stories, jokes, anecdotes, videos—throughout the presentation.

Every time you introduce a new stimulus or media, the attention peaks in the audience. Our brains look for novelty, and if it's different, we can't help but listen up.

Putting in multimedia elements--such as videos and visuals--reinforces the content for visual learners in addition to mixing up the presentation format. Video and visuals can be great speaker support as well.

Stories, anecdotes, relevant jokes and metaphors are naturally engaging formats; they reinterpret information in a different way--so it's like a review within a presentation--and they add relevance and personality to the content or data.

3. Save the year-in-review for the middle of the presentation.

This is one of the most frustrating things that we see in corporate presentations.

The stage is set--this event is going to be new and different, they say. The audience is in a new ballroom and they're prepared--nay, they're *expecting*--to be motivated. . .

And then the first executive starts his speech with an inspiring. . . year-in-review. We're not saying that the year-in-review isn't important--indeed, it's crucial to know where you've been so you can see where you're going, and it's certainly important to highlight past successes to motivate the group. However, the past shouldn't be the first thing in a "brand-new" event.

Aside from that, though, is that the audience already *knows* (or should know), basically, what already happened. Therefore, it shouldn't take up prime attention real-estate at the beginning of a presentation. Instead, review current topics/goals, and then put the year-end review in the middle of the presentation in the context of future plans/actions and learnings.